Giant kille

By WANG XING (China Daily) Updated: 2008-10-20 07:30

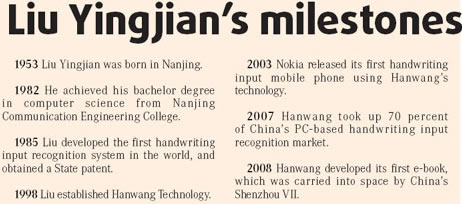

In China's dynamic high technology industry dominated by young entrepreneurs in their 20s and 30s, 55-year-old Liu Yingjian might seem eccentric. But that has not prevented him from leading one of the most successful domestic technology firms in China, Hanvon Technology.

In China's dynamic high technology industry dominated by young entrepreneurs in their 20s and 30s, 55-year-old Liu Yingjian might seem eccentric. But that has not prevented him from leading one of the most successful domestic technology firms in China, Hanvon Technology.As the company's founder and CEO, Liu, born in 1953, keeps changing his mobile phone every four months. He has two iPod music players and showed great enthusiasm for Super Girl, an American Idol copycat that attracted millions of frenzied young people across China in 2005.

On his office desk lay two dismembered Wii Remotes, the wireless controller of the popular Wii game console that Liu bought for research. The Wii console is famous for its ability to detect players' movements in three dimensions.

It may be Liu's sensitivity and tech savvy sensibilities in keeping up with the latest industry trends that make his company, Hanvon Technology, stand out.

Though many of its peers established in the 1990s sank into obscurity after foreign giants such as Motorola, Nokia and Microsoft start tapping the Chinese market, Hanvon Technology, China's first handwriting-input recognition firm, has survived and thrived.

During the past 10 years, it has successfully staved off Motorola and forced Microsoft to give up the idea to embed its own handwriting recognition software into its mobile operating systems.

Last year, Hanvon's software was adopted in over 130 handsets made by companies like Nokia and Motorola and its technology was even used in the lateste version of Apple Inc's iPhone.

"I think we can still survive today mainly because we have our own intellectual property and have been extremely focused on our core business," Liu says.

First deal

As the pioneer in Chinese handwriting recognition technology, Liu's business can be traced back to 1984, when he invented the world's first computerized handwriting-input pen. But his first order didn't come until 1992 when he showed his technology at a software industry exhibition in Hong Kong.Liu's handwriting recognition technology did not receive much attention at the expo, but a young man from Hong Kong showed special interest in it and invited him to dinner later that night.

"In order to impress me, he told me there would be a Rolls-Royce picking me up after the exhibition, but in fact at that time I had no idea about that name at all," says Liu.

The young man, Xue Defa, was the founder of Zhongshan Meijin Computer Technology, one of China's largest PDA (Personal Digital Assistant) and electronic dictionary manufacturers. At that time, Xue was puzzling over rolling out a revolutionary PDA product that could enable users to input information on the small digital device without a keyboard. And Liu's handwriting input recognition technology seemed to be the perfect solution.

After short discussion, Xue and Liu agreed to cooperate and Liu got his first deal, worth $100,000.

Boosted by Meijin, Liu's offers started to increase in the following years and the new business had Liu, his team and pregnant wife working day and night to fill the orders. In order to protect his wife from computer radiation, Liu also stripped a bronze plate from a hot-pot to cover her belly.

When Liu's baby was born he named the baby "Tong Tong" (tong means bronze in Chinese) in memory of those early business days.

"It was a hard time but it also helped build a solid foundation for our future development," says Liu.

In the following years, Hanvon prospered from licensing the technology to other partners and releasing its own branded products, such as the Chinese-input recognition pen, which became very popular among users who were uncomfortable with a standard alphabetical computer keyboard.

Motorola arrives

However, as Liu's business continued to growth, foreign competitors also entered the market.In 1997, mobile phone maker Motorola, which had acquired an English-input recognition company in the United States, started to develop Chinese input recognition technology and released products that directly competed with Hanvon Technology's input-recognition pen in China.

In order to erode Hanvon's market share, Motorola launched a series of aggressive advertising champions and started promoting the products through its existing national distribution channel in the country.

"I was shocked by their marketing. They had a strong brand, a wide distribution channel and huge capital support from the headquarters," says Liu. "All the factors were against us at that time."

In order to fend off Motorola, Liu turned to IBM and spent $400,000 to buy the company's voice recognition technology IBM Viavoice, which was still not fully mature at that time. He then combined it with Hanvon's existing products and released a series of new versions that supported both writing and voice recognition.

Liu also start expanding Hanvon's distribution channels and gradually established retail networks across China in the following years.

Boosted by these measures, sales of Hanvon's input recognition pen increased over 200 percent in 1998 and two years later Motorola quit the market.

"The war with Motorola was the most difficult time for us," says Liu. "But the competition also helped to boost the market and made more people know about handwriting-input products."

War over monopoly

Almost the same time that Hanvon was fighting with Motorola, the more powerful American technology giant Microsoft also entered the market.In December 1998, Hanvon and Microsoft signed a partnership in which Hanvon would license its technology to Microsoft's Windows CE operating system that is used in consumer digital devices.

However, Liu later learned that Microsoft intended to imbed its own handwriting-recognition technology in its then upcoming Microsoft Windows 2000 operating system.

As the dominating operating system provider, Microsoft has the ability to destroy other independent software vendors. For instance, the market share of what was once the world's largest web browser company Netscape declined significantly after Microsoft imbedded its own Internet Explorer in the Windows operating system free of charge.

"If Microsoft imbedded its handwriting recognition technology into its own software, we couldn't survive," says Liu. "So we started negotiations with them." At the same time, Liu also aggressively expanded its speed in rolling out new hardware products to strengthen its independent status.

As a result, Microsoft dropped its plan to imbed its own technology in the Windows CE and Windows Mobile system in China and used Hanvon's technology instead. But it still imbedded its technology into its later Windows and Office products.

Diversification

After the war with Motorola and Microsoft, Hanvon started to diversify its product lines in order to expand its business outside a single market sector.From 1999 to 2004, the company expanded into areas such as banking personal identification recognition systems, automotive license plate recognition systems and the optical character recognition market.

Although some of the new programs failed, the diversity gave Hanvon a broader growth base and significantly helped expand its product lines.

From 2003 to 2007, Hanvon's revenue increased at an average growth rate of 27 percent and its revenue last year reached 234 million yuan. The company's business in oversea markets also increased significantly.

Liu says his plan is to see Hanvon ranked in the world's top 500 companies in the future and that opportunity lies in the rise of interactive intelligence.

"Whether it is handwriting recognition or optical character recognition, it is about interactive intelligence," says Liu. "In the next 10 years, the development of interactive intelligence will create a huge market and we are both confident and patient with that."